The Royal Photographic Society Journal

RPS Journal - Jan/Feb 2023 - Words and images by Kathleen Morgan / Alex Boyd

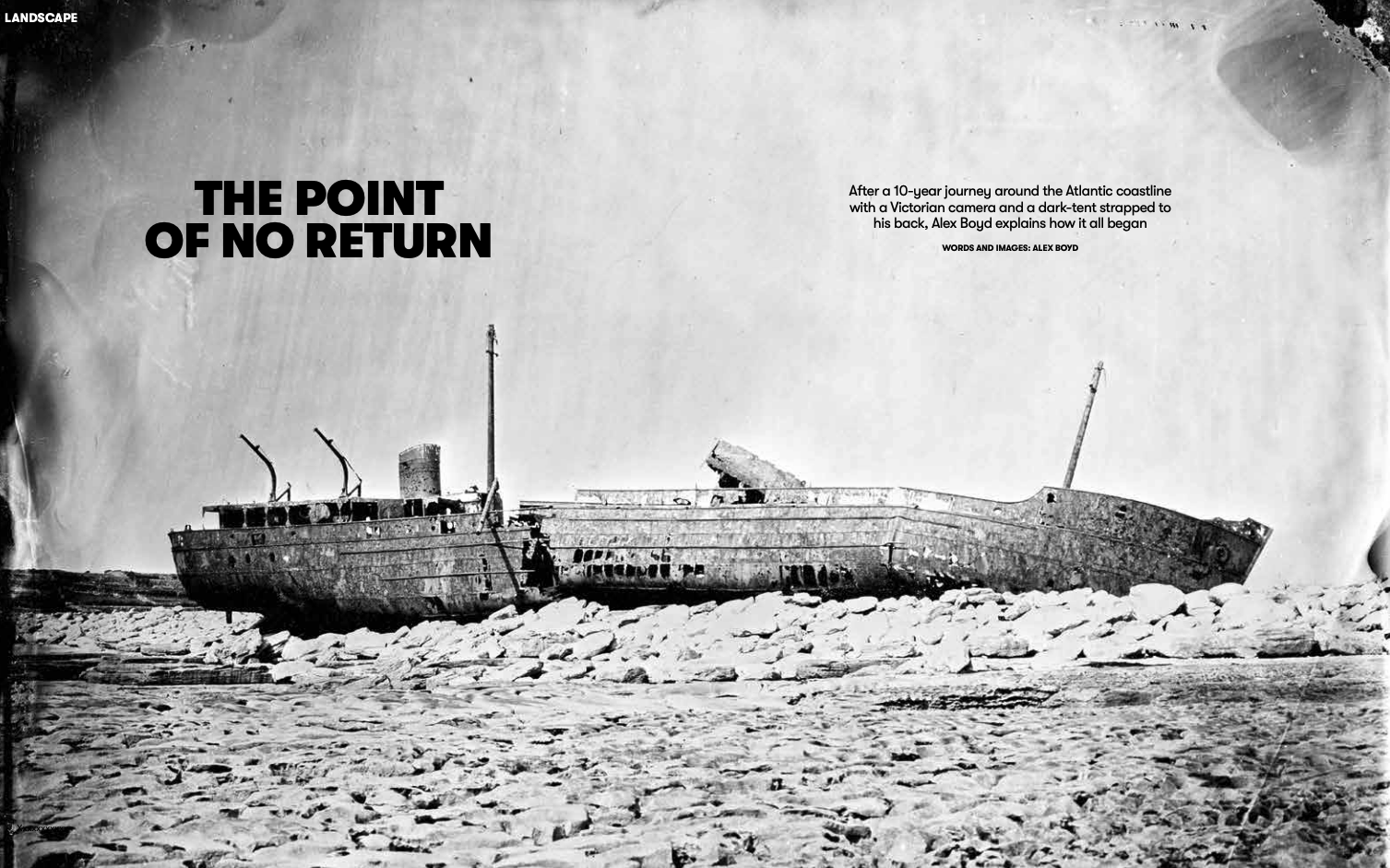

As a young man Alex Boyd would gaze across the Irish sea from his native Scotland to the landscape beyond. In 2012, when he was in his late twenties, he made the journey in real life rather than in his imagination. Arriving at Pointe a’ Tárrthaidh, or The Point of the Deliverance – a headland in the harbour of Portacloy, County Mayo – Boyd began making images using the wet collodion process. Invented by Frederick Scott Archer in 1848, the technique has since become Boyd's trademark. The photographer and printmaker has earned recognition for exploring landscape, identity and land ownership – as well as for his collaborations with musician Nick Cave and the late Scottish poet Edwin Morgan. Now, Boyd has completed a ten-year visual journey around the coasts of Scotland and Ireland. As 70 images from the series are published in the book The Point of the Deliverance, he describes how it all began.

It’s hard to pinpoint that exact moment. The moment I decided I would strap to my back a field camera, glass and enough chemistry to make a few images. A dark-tent and a tripod completed the look – and would eventually take its toll on my posture. If I was lucky, as I often was, a friend would accompany me to share the weight. A good place to start is 2010, when I visited the incredible show The Family and the Land by Sally Mann at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. I was immediately drawn to her scratched, freckled and ghostly images of the American south. An antique Victorian process would now enter my life, and thanks to a workshop in Glasgow I was ready to try it myself outside the relative safety of the studio. The technique, wet-plate collodion, is an involved one. The photographer makes images by pouring a thick, sweet smelling, chemical called collodion onto pieces of tin or glass.

These are then dipped into a bath of silver, then loaded into the back of a camera. After pointing the camera at the subject and making your exposure, the image is then opened in a dark place, developed, then fixed, often using cyanide. From start to finish you have only ten minutes to make and develop the image, hence the name wet-plate. Once the chemicals dry the image is essentially unworkable, meaning the darkroom must travel with you – as it did with early practitioners in the 1850s and 1860s. In the confines of a studio, it's much easier than it sounds and becomes second nature. Doing it on the side of a mountain, or in an exposed landscape under assault from the local insect population, the weather, or both, is much more challenging. I was drawn to the wild Atlantic coastline of the British Isles, to Scotland and Ireland, for The Point of the Deliverance, a ten-year project involving travel from Cape Wrath to Kerry, now published as a book of the same name. Some days, such as those spent on the Aran Islands, were a joy while others, such as on Lewis and Harris, could be far more challenging. On the slopes of Carrauntoohil, the highest mountain in Ireland, I was defeated by exhaustion and the terrain. The hardest days of all lay on Skye, where I dragged myself up into the peaks of the Cuillin mountains to make images, having spent a month practising in the north of the island in the surreal landscapes of the Storr and the Quirang. Working this way allows me to explore an aesthetic which often creates quite brooding images.

For example, if I want to make the landscapes more abstract, or to create dramatic blackened skies, my hands work quickly to burn the images with chemical spills, or to darken the skies. Each is a reflection of my mood on the day, an attempt to capture what many have termed ‘thin places’, where the actual meets the spiritual and where cartography seems less certain. It is an approach which would likely have made the Victorian photographers who used this process recoil in horror. It all came together on the image ‘Last light, Dún Briste’, made at Downpatrick Head in Ireland. Using a Second World War bunker as an improvised darkroom, I worked all day to capture something of the strangeness of the location, where a ruined chapel for St Patrick sits alongside Poll na Scantoine, a vast blowhole where the sea roars up from a tunnel directly beneath you. As you stare out to the Atlantic, the sea stack Dún Briste (the Broken Fort) looms ahead. Following hours of failed attempts, I finally made a successful picture with trembling, black-stained hands, the cliffs and stack illuminated in a lightning flash of developer. It was a moment of pure euphoria when the image appeared before me in the developer tray, a feeling perhaps only slightly enhanced by the effects of working with ether all day.

You can download the original article (with images) here.